Introduction to Psychometric Models

Lecture 2

Today’s Lecture Objectives

- An Framing Example

- Latent traits

- Our first graphical model (path diagram)

- Psychometric models from generalized linear models

Class Discussion: Satisfaction with Life Scale

Take a look at the following items (as reported in McDonald, 1999): https://uiowa.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_6J8Hakox1U4S7UW

Questions for discussion:

- How would we analyze these data?

- Do you know of any psychometric model that would work?

More Class Discussion: SWLS, Revised

Now, take a look at the following revised items (item stems reported in McDonald, 1999): https://uiowa.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_e8rqrilRNBnT8SG

Questions for discussion:

- What is different about this survey?

- Does this survey seem to measure the same construct as the previous survey?

- How would we analyze these data?

- Do you know of any psychometric model that would work?

Latent Traits: A Big-Picture View

Latent trait theory posits there are attributes of a person (typically) that are:

- Unobservable (hence the term latent)

- Quantifiable

- Related to tasks that can be observed

Often, these attributes are often called constructs, underscoring they are constructed and do not exist, such as:

- A general or specific ability (in educational contexts)

- A feature of personality, such as “extroversion” (in psychological contexts)

The same psychometric models apply regardless of the measurement context (math don’t care)

The Long History of Latent Trait Theory

- Latent trait theory, as we now know it, began well before most current academic disciplines

- Educational assessments (tests) have existed for centuries

- These seek to measure latent abilities

- The study of intelligence began in the mid 1800s

- Intelligence is also a latent trait

- Educational assessments (tests) have existed for centuries

- Methodological innovations have often spurred empirical (discipline-specific) trait development

- Early methods were limited by mathematical and statistical theory

- The invention and wide-spread use of computers made advances in psychometrics possible

- More recent statistical innovations further shape methods (i.e., computational estimation methods using Bayes)

Latent Traits are Interdisciplinary

- Many varying fields use some version of latent traits

- Similar (or identical) methods are often developed separately

- Item response theory in education

- Item factor analysis in psychology

- Many different terms for same ideas, such as the

- Label given to the latent trait: Factor/Ability/Attribute/Construct

- Label given to those giving the data: Examinee/Subject/Participant/Respondent/Patient/Student

- What this means:

- Lots of words to keep track of, but (relatively) few concepts

- We will focus on concepts (but have a lot of words)

The Best Constructs Are Built Purposefully

- Latent constructs seldom occur randomly—they are defined

- The definition typically indicates:

- What the construct means

- What observable behaviors are likely related to the construct

- For a lot of what we do, observable behavior means answering questions on an assessment or survey

- The definition typically indicates:

- Therefore, modern psychometric methods are built around specifying the set of observed variables to which a latent variable relates

- No need for exploratory analyses—we define our construct and seek to falsify our definition

- The term I use for “relates” is “measure”

- Educational assessment items measure some type of ability

Guiding Principles

- To better understand psychometric methods and theory, I recommend you envision what you would do if latent variables were not latent

- Example: Imagine if we could directly observe mathematics ability

- Then, consider what we would do with that value

- Example: We could predict how students would perform on items using logistic regression

- Psychometric models essentially do this—use observed variable methods as if we know the value of the latent variable

- There are some catches, though

- We need a data collection design that allows for such methods to be used

- We need a more formal vetting of whether or not we did a good job measuring the construct

- There are some catches, though

Measurement, Formally Defined

Measurement is the quantification of some characteristic (physical or otherwise)

- Consider the measurement of length (a physical construct)

- Why? We need to know where to put things

- How? We use some type of device (a ruler, yardstick, tape measure) and note the distance from the origin

- What? The distance is then quantified with some type of unit (a unit of measure)

- Inches, centimeters, meters, yards, etc…

Measurement of Latent Constructs

- How does this differ when we cannot observe the thing we are measuring—when the construct is latent?

- We still need something we can observe—item responses for example

- We need a method to map the response to a number (like the inches)

- Strongly agree==5?

- We also need a way to aggregate all responses to a value that represents a person

- A score or classification

- We then need a way to ensure what we just did means what we think it does

- Methods for validation

- We also need to remember that the values we estimate for the latent variable won’t be perfectly reliable

- Caution needed for secondary analyses

Measurement Models

- A distinguishing feature of psychometric models is the second word—they are models

- We often call such models “measurement models”

- Measurement models are the mathematical specification that provides the link between the latent variable(s) and the observed data

- The form of such models looks different across the wide classes of measurement models (e.g., factor analysis vs. item response models) but wide generalities exist

- Measurement models need:

- Distributional assumptions about the data (with link functions)

- A linear or non-linear form that predicts data from the trait(s)

- The key: Observed data are being predicted by latent variable(s)

Measurement Models vs. Other Measurement Techniques

Measurement models are a different way of thinking about psychometrics than what most people without psychometric training do

- A lot of the world will enumerate item response scores

- e.g., correct response == 1; strongly agree == 5

- The latent trait score estimate is then formed by adding the response scores together

- The “Add Stuff* Up” model

- Please see Lesa Hoffman for a more explicit definition of Stuff

- The “Add Stuff* Up” model

- As it turns out, the naïve adding together of item scores implies a measurement model

- Called parallel items — very strict assumptions (equal variances and covariances)

Characteristics of Latent Variables

Characteristics of Latent Variables

- Latent variables can have different levels of measurement (in concept, not in practice)

- Interval level (as in factor analysis and item response theory) — Continuous

- No absolute zero, but units of the quantity are equivalent across the range of values

- Example: A person with a value of 2 is the same distance from a person with a value of 0 as is a person with a value of -2

- Ordinal level (as in diagnostic classification models)

- Can rank order people but not determine how far apart they may be

- Example: Students considered masters of a topic have more ability than students considered non-masters

- Nominal level (as in latent class or finite mixture models) — Categorical

- Groups/classes/clusters of people

- No scale provided at all

- Interval level (as in factor analysis and item response theory) — Continuous

Most Common: Continuous Latents

- For most of this class, we will treat latent variables as continuous (interval level)

- As they do not exist, continuous latent variables need a defined metric:

- What is their mean?

- What is their standard deviation?

- Defining the metric is the first step in a latent variable model

- Called scale identification

- The metric is arbitrary

- Can set differing means/variances but still have same model

- Linear transformations of parameters based on scale mean and standard deviation

Measurement Model Path Diagrams

Measurement models are often depicted in graphical format, using what is called a path diagram

- Typically, latent variables are represented as objects that are circles/ovals

- Using graph theory terms, a variable in a path diagram (latent or observed) is called a node

- Lines connecting the variables are called edges

Latent Variable Only

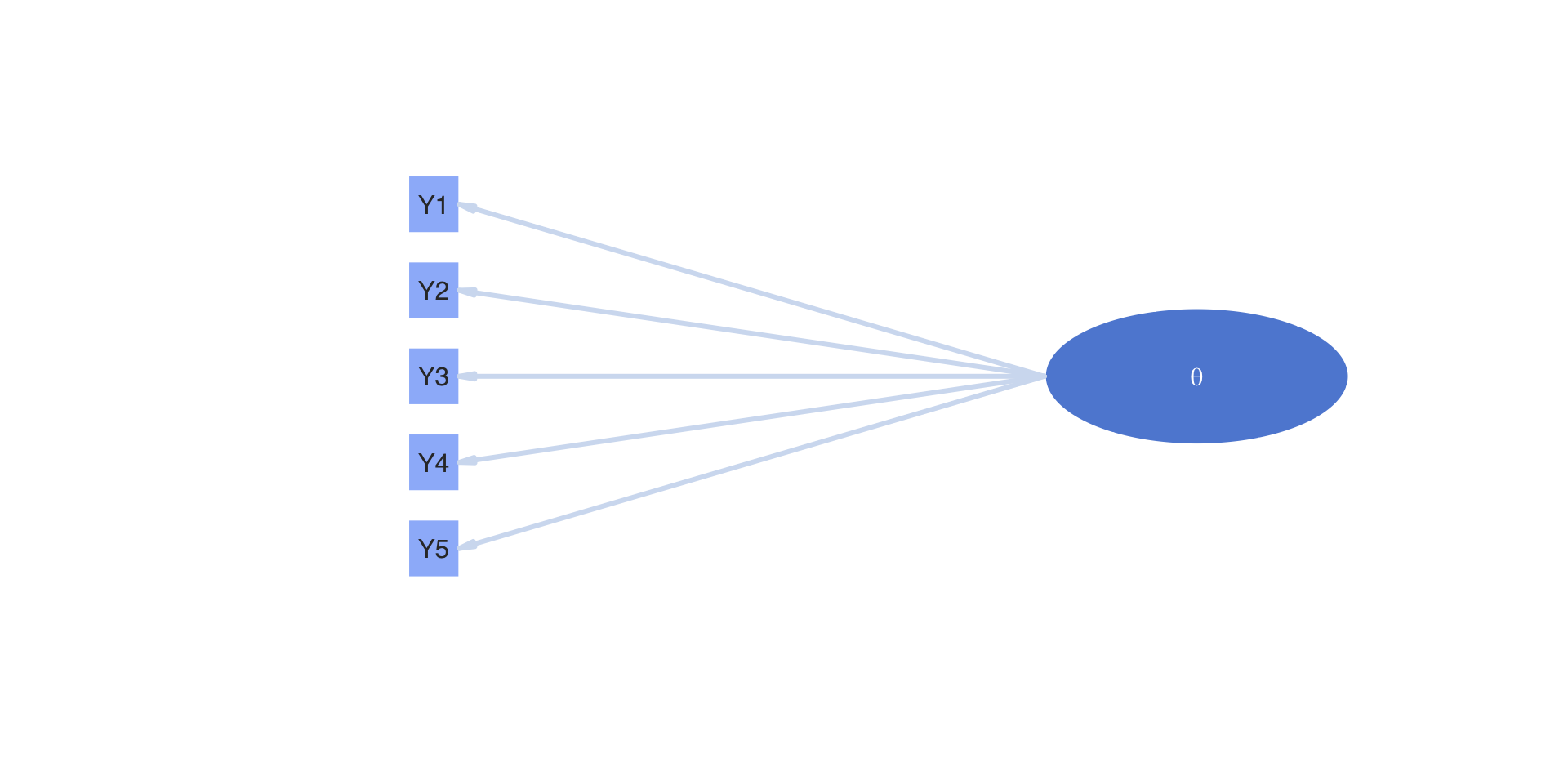

Adding Observed Variables

Measurement model path diagrams often denote observed variables with boxes

On the next slide:

- The term “latent variable” is replaced with \(\theta\)

- The observed variables are denoted as \(Y1\) through \(Y5\)

- Imagine these represent the five items of the scale we started class with

Path Diagram with Observed and Latent Variables

Path Diagrams: Not Models

Path diagrams are useful for depicting a measurement model but are not models

- All model parameters cannot be included in the diagram

- No indication about the distribution of the variables (especially needed in Bayesian psychometric modeling)

Translating a Path Diagram to a Model

Going back to our the point from before—let’s imagine the latent variable as an observed variable

- An arrow (edge) indicates one variable predicts another

- The predictor is the variable on the side of the arrow without the point

- The outcome is the variable on the side of the point

- If we assume the items were continuous (like linear regression), the diagram indicates a regression model for each outcome

\[ \begin{array}{c} Y_{p1} = \beta_{Y_1, 0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_1} \\ \end{array} \]

Interpreting the Parameters

All five regression lines implied by the model are then:

\[ \begin{array}{c} Y_{p1} = \beta_{Y_1, 0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_1} \\ Y_{p1} = \beta_{Y_2, 0} + \beta_{Y_2,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_2} \\ Y_{p3} = \beta_{Y_3, 0} + \beta_{Y_3,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_3} \\ Y_{p4} = \beta_{Y_4, 0} + \beta_{Y_4,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_4} \\ Y_{p5} = \beta_{Y_5, 0} + \beta_{Y_5,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_5} \\ \end{array} \]

Here:

- \(\beta_{Y_i, 0}\) is the intercept of the regression line predicting the score from item \(Y_i\)

- The expected resposne score for a person who has \(\theta_p=0\)

- \(\beta_{Y_i, 1}\) is the slope of the regression line predicting the score from item \(Y_i\)

- The expected change in the response score for a one-unit change in \(\theta_p\)

More Interpreting the Parameters

Also:

- \(e_{p, Y_i}\) is the residual (error), indicating the difference in the predicted score for person \(p\) to item \(i\)

- Like in regression, we additionally assume:

- \(e_{p,Y_i} \sim N\left(0, \sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}} \right)\): is normally distributed with mean zero and…

- Like in regression, we additionally assume:

- \(\sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}}\) is the residual variance of item \(Y_i\), indicating the square of how far off the prediction is on average

The five regression models are estimated simultaneously:

- If \(\theta_p\) were observed, we would call this a multivariate regression

- Multivariate regression: Multiple continuous outcomes predicted by one or more predictors

More About Regression

\[Y_{pi} = \beta_{Y_i, 0} + \beta_{Y_i,1} \theta_p + e_{p, Y_i} \]

In the regression model for a single variable, what distribution do we assume about the outcome?

- As error is normally distributed, the outcome takes a normal distribution \(Y_{pi} \sim N( ?, ?)\)

- As \(\beta_{Y_i, 0}\), \(\beta_{Y_i,1}\), and \(\theta_p\) are constants, they move the mean of the outcome to \(\beta_{Y_i, 0} + \beta_{Y_i,1} \theta_p\)

- \(Y_{pi} \sim N( \beta_{Y_i, 0} + \beta_{Y_i,1} \theta_p, ?)\)

- As error has a variance of \(\sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}}\), the outcome is assumed to have variance \(\sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}}\)

- \(Y_{pi} \sim N( \beta_{Y_i, 0} + \beta_{Y_i,1} \theta_p, \sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}})\)

- Therefore, we say \(Y_{pi}\) follows a conditionally normal distribution

The Univariate Normal (Gaussian) Distribution

- When we say \(Y \sim N( \mu, \sigma^2)\), that implies a probability density function (pdf).

- For the univariate normal (sometimes called Gaussian) distribution, the pdf is: \[f\left(Y\right) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2 }}\exp\left[\frac{\left(Y - \mu \right)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right]\]

- Here, \(\pi\) is the constant 3.14 and \(\exp\) is Euler’s constant (2.71)

- Of note here is that there are three components that go into the function:

- The data \(Y\)

- The mean \(\mu\) — this can be the conditional mean we had on the previous slide (formed by parameters)

- The variance \(\sigma^2\)

- The key to using Bayesian methods is to know the distributions for each of the variables in the model

From Regression to CFA

When \(\theta_i\) is latent, the five-variable model becomes a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model

- CFA: Prediction of continuous items using linear regression with one or more continuous latent variables as predictors

- The interpretations of the regression parameters are identical between linear regression and CFA

Regression and CFA Differences

The differences between CFA and regression are:

- \(\theta_p\) is not observed in CFA but is observed in regression

- Therefore, we must set its mean and variance

- There are multiple was to do this (standardized factor, marker item, etc…)—stay tuned

- Therefore, we must set its mean and variance

- Each of the model parameters has a different name (and symbol denoting it) in CFA

- \(\beta_{Y_i, 0} = \mu_i\) is the item intercept

- \(\beta_{Y_i,1} = \lambda_i\) is the factor loading for an item

- \(\sigma^2_{e_{Y_i}} = \psi^2_i\) is the unique variance for an item

- We must have a sufficient number of observed variables to empirically identify the latent trait

Changing Notation

Our five-item CFA model with CFA-notation:

\[ \begin{array}{c} Y_{p1} = \mu_1 + \lambda_1 \theta_p + e_{p, Y_1} \\ Y_{p2} = \mu_2 + \lambda_2 \theta_p + e_{p, Y_2} \\ Y_{p3} = \mu_3 + \lambda_3 \theta_p + e_{p, Y_3} \\ Y_{p4} = \mu_4 + \lambda_4 \theta_p + e_{p, Y_4} \\ Y_{p5} = \mu_5 + \lambda_5 \theta_p + e_{p, Y_5} \\ \end{array} \]

Measurement Models for Different Item Types

Measurement Models for Different Item Types

The CFA model assumes (1) continuous latent variables and (2) continuous item scores

- What should we do if we have binary items (e.g., yes/no, correct/incorrect)?

If we had observed \(\theta_p\) and wanted to predict \(Y_{1p} \in \{0,1\}\) (read as \(Y_{p1}\) takes values of either zero or one) what type of analysis would we use?

Logistic regression:

\[P\left(Y_{p1} = 1\right) = \frac{\exp \left( \beta_{Y_1,0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p\right)}{1+\exp \left( \beta_{Y_1,0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p\right)}\]

Alternatively: \[Logit \left( P\left(Y_{p1} = 1\right) \right) = \beta_{Y_1,0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p\]

Interpreting of Model Parameters

\[Logit \left( P\left(Y_{p1} = 1\right) \right) = \beta_{Y_1,0} + \beta_{Y_1,1} \theta_p\]

Here:

- \(\beta_{Y_1,0}\) is the intercept — the expected log odds of a correct response when \(\theta_p = 0\)

- \(\beta_{Y_1,1}\) is the slope — the expected change in log odds of a correct response for a one-unit change in \(\theta_p\)

- Note: there is no error variacne term…why?

Bernoulli Distributions

- Using logistic regression for binary outcomes makes the assumption that the outcome follows a (conditional) Bernoulli distribution, or \(Y \sim B(p_Y)\)

- The parameter \(p_Y\) is the probability that Y equals one, or \(P\left(Y = 1\right)\)

- The Bernoulli pdf (sometimes called the probability mass function as the variable is discrete) is: \[f(Y) = \left(p_Y\right)^Y \left(1-p_y \right)^{1-Y}\]

- So, there is no error variance parameter in logistic regression as there is no parameter in the distribution that represents error.

- Error is represented by how far off a probability is from either zero or one

Logistic Regression with Latent Variable(s)

- Back to our running example, if we had binary items and wished to form a (unidimensional) latent variable model, we would have something that looked like:

\[P\left(Y_{pi} = 1 \mid \theta_p \right) = \frac{\exp \left( \mu_i + \lambda_i \theta_p\right)}{1+\exp \left( mu_i + \lambda_i \theta_p\right)}\]

- Here, the parameters retain their names from CFA:

- \(\beta_{Y_i, 0} = \mu_i\) is the item intercept

- \(\beta_{Y_i,1} = \lambda_i\) is the factor loading for an item

- We call this slope-intercept parameterization

- This parameterization is called item factor analysis(IFA)

From IFA to IRT

- IFA and IRT are equivalent models—their parameters are transformations of each other:

\[ \begin{array}{c} a_i = \lambda_i \\ b_i = -\frac{\mu_i}{\lambda_i} \end{array} \]

- This yields the discrimination-difficulty parameterization that is common in unidimensional IRT models:

\[P\left(Y_{pi} = 1 \mid \theta_p \right) = \frac{\exp \left( a_i\left( \theta_p -b_i\right)\right)}{1+\exp \left(a_i\left( \theta_p -b_i\right)\right)}\]

- \(b_i\) is the item difficulty—the point on the \(\theta\) scale at which a person has a 50% chance of answering with a one

- \(a_i\) is the item discrimination—the slope of a line tangent to the curve at the item difficulty

- IRT models have a number of different forms of this equation (this is the two-parameter logistic 2PL model)

Generalized Linear (Psychometric) Models

- A key to understanding the varying types of psychometric models is that they must map the theory (the right-hand side of the equation—\(\theta_p\)) to the type of observed data

- Today we’ve seen two types of data: continuous (with a normal distribution) and binary (with a Bernoulli distribution)

- For each, the right-hand side of the item model was the same

- For the normal distribution:

- We had an error term but did not transform the right-hand side

- For the Bernoulli distribution:

- No error term and a function used to transform the right-hand side so that the conditional mean ranged between zero and one

- We will use these features in each of our models as we continue in this class

- This is also an introduction to generalized linear models

Wrapping Up

- This lecture was a quick introduction to psychometric models

- Latent trait theory guides the construction of items

- Psychometric models then implement and test the theory

- The family of model used is determined by the type of observable data