An Introduction to Regularization Methods

Introduction

Section 1: The Problem with “Best Fit”

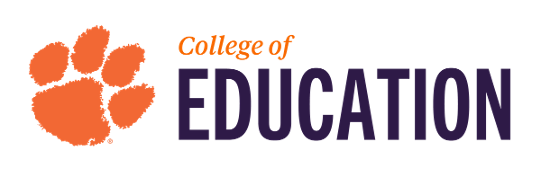

Changing Landscape of Data

- Traditional Research: Small \(N\) (participants), Small \(p\) (variables).

- Focus: Theory-driven hypothesis testing.

- The New Reality: “Wide” Data: Log-trace data, dense surveys, genomic markers.

- High-Dimensional Prediction: \(p\) is large relative to \(N\).

- The Consequence: Traditional methods like OLS struggle to distinguish signal from noise.

The Status Quo: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)

- The Gold Standard: OLS is designed for inference in large samples with few predictors.

- The Objective: Unbiased estimates with minimum standard error.

- The Mechanism: Minimizes the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS).

- It tries to pass a line strictly through the “center” of the data points.

The OLS Trap in High Dimensions

- Capitalizing on Chance: When predictors (\(p\)) are many, OLS finds spurious relationships by chance.

- Overfitting: The model “memorizes” the training data rather than learning the underlying pattern.

- The Symptom: Excellent fit on current data (\(R^2\) is high).

- Poor performance on new data (Prediction fails).

Visualizing the Problem

- Left: OLS works well with sparse data.

- Right: As dimensions expand, the connections become too complex for simple minimization.

The Goal: Generalizability

- Shift in Perspective: Moving from “Is this coefficient significant?” to “Does this model generalize?”.

- The Trade-off: To improve prediction on future data, we must accept some error on current data.

- The Solution: We need a mathematical way to constrain the model—to stop it from chasing noise.

Concept

Section 2: The Solution - Regularization

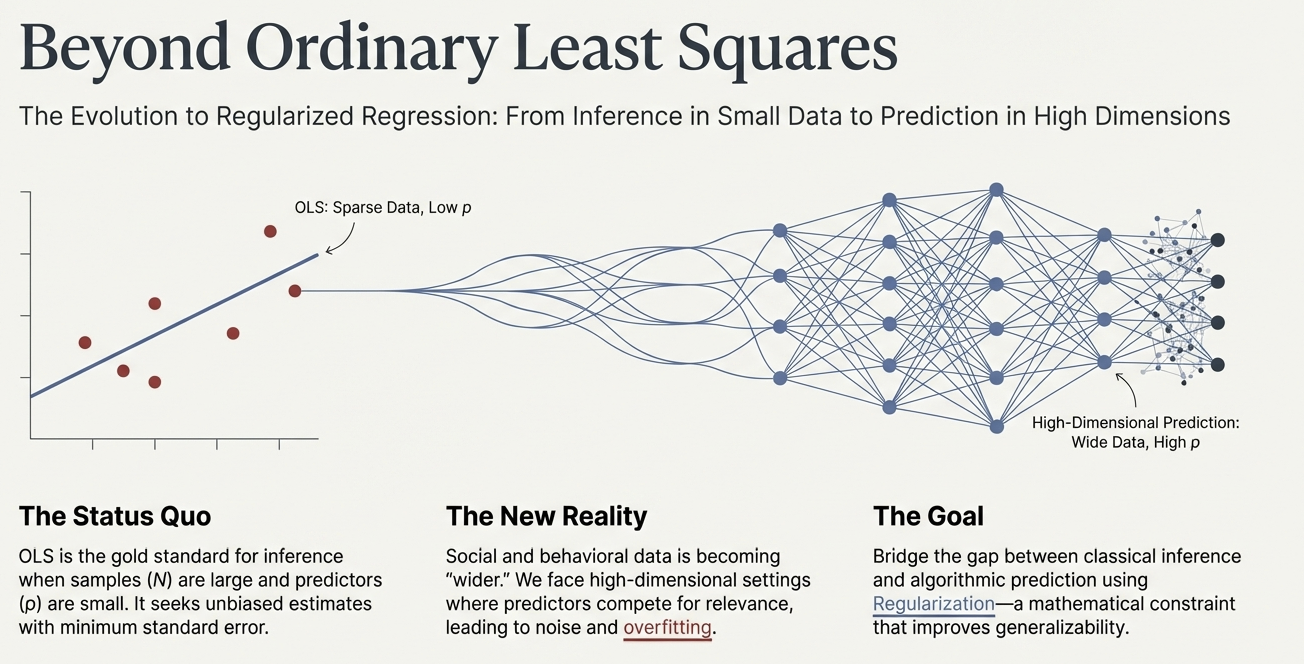

The Bias-Variance Trade-off

- Bias: Error from erroneous assumptions (e.g., missing a relationship).

- Variance: Error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set.

- The Conflict: OLS = Low Bias, High Variance.

- Regularization = Higher Bias, Low Variance.

Introducing “Bias” Intentionally

- Why Add Bias? By restricting the model, we stabilize the estimates.

- We prevent the model from reacting to random noise.

- The Result: A model that is slightly “wrong” on average (biased) but consistently closer to the truth (low variance) across different samples.

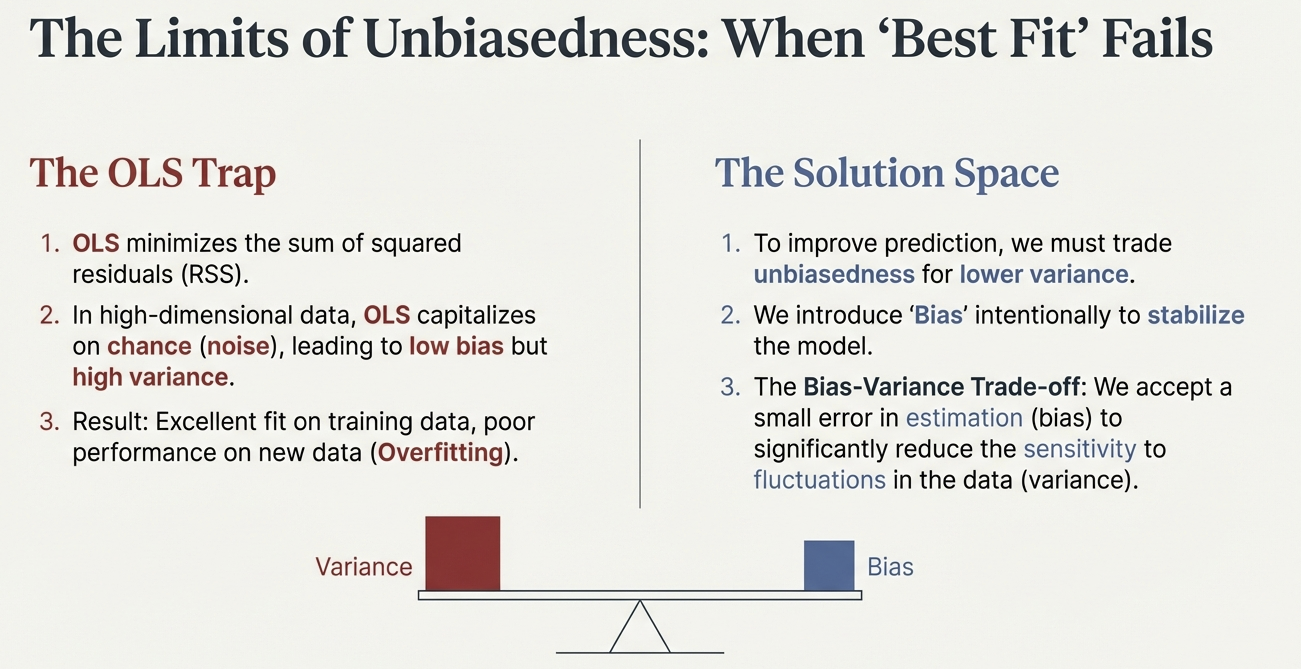

The Math: Redefining the Cost Function

\[\text{Regularized Cost} = \text{[RSS] or [-LL]} + \text{Penalty}\]

- RSS: The standard OLS term (Fit the data).

- Penalty: The constraint term (Keep coefficients small).

- The Mechanism: The model must “pay” a price for every coefficient it estimates.

The Specifics: Linear Models with OLS

The least squares cost function:

\[\text{RSS} = \sum_{p=1}^{N}\left(Y_p - \left(\beta_0 + \sum_{i=1}^{p} \beta_i X_{ip}\right)\right)^2\]

The Specifics: Generalized Linear Models with Maximum Likelihood

The ML likelihood function:

\[\text{LL} = \sum_{p=1}^{N} \log P(Y_p | X_p, \boldsymbol{\beta})\]

- Here, \(P(Y_p | X_p, \boldsymbol{\beta})\) is the PDF of the outcome

The Cost Function

\[\text{Regularized Cost} = \text{[RSS] or [-LL]} + \text{Penalty}\]

- Penalty: A function of the coefficients (\(\beta\)s) that increases as coefficients grow.

- Types of Penalties:

- Ridge Regression: \(\lambda \sum_{i=1}^{P} \beta_i^2\) (L2 norm)

- LASSO: \(\lambda \sum_{i=1}^{P} |\beta_i|\) (L1 norm)

- Elastic Net: \(\lambda \left(\alpha \sum_{i=1}^{P} |\beta_i| + (1-\alpha) \sum_{i=1}^{P} \beta_i^2\right)\)

NOTE: \(\lambda\) and \(\alpha\) are set by the user (and typically ranges of \(\lambda\) are tested)

- The Goal: Minimize the Regularized Cost by choosing optimal \(\beta\)s.

The Tuning Parameter: Lambda (\(\lambda\))

- Lambda (\(\lambda\)): Controls the strength of the penalty.

- \(\lambda = 0\): No penalty. The result is identical to OLS.

- High \(\lambda\): Strong penalty. Coefficients are shrunken heavily toward zero (High Bias).

- The Goal: Find the “Goldilocks” \(\lambda\)—not too simple, not too complex.

Techniques

Section 3: Ridge Regression

Ridge Regression (\(L_2\) Penalty)

- The Formula: Adds the sum of squared coefficients to the cost function. \[\dots + \lambda \sum \beta^2\]

- Behavior: Shrinks coefficients toward zero but rarely sets them exactly to zero.

- “Democratic” shrinkage: It reduces the impact of all variables proportionally.

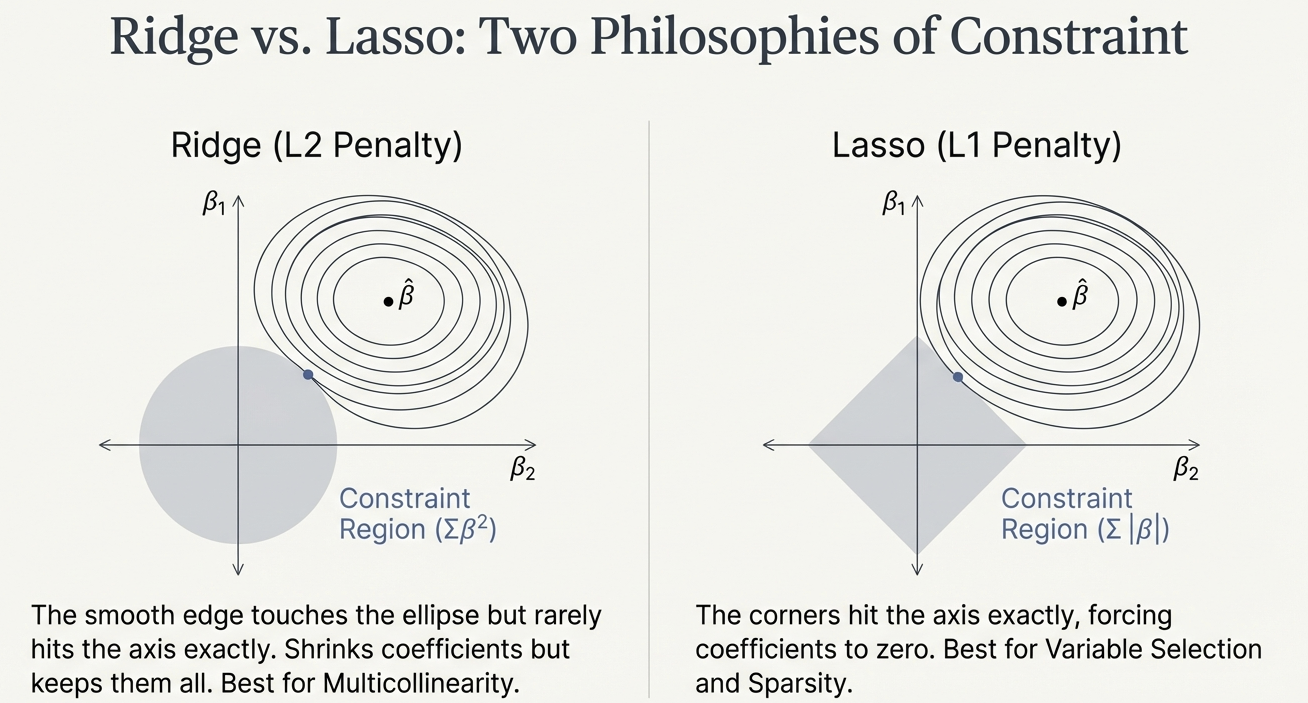

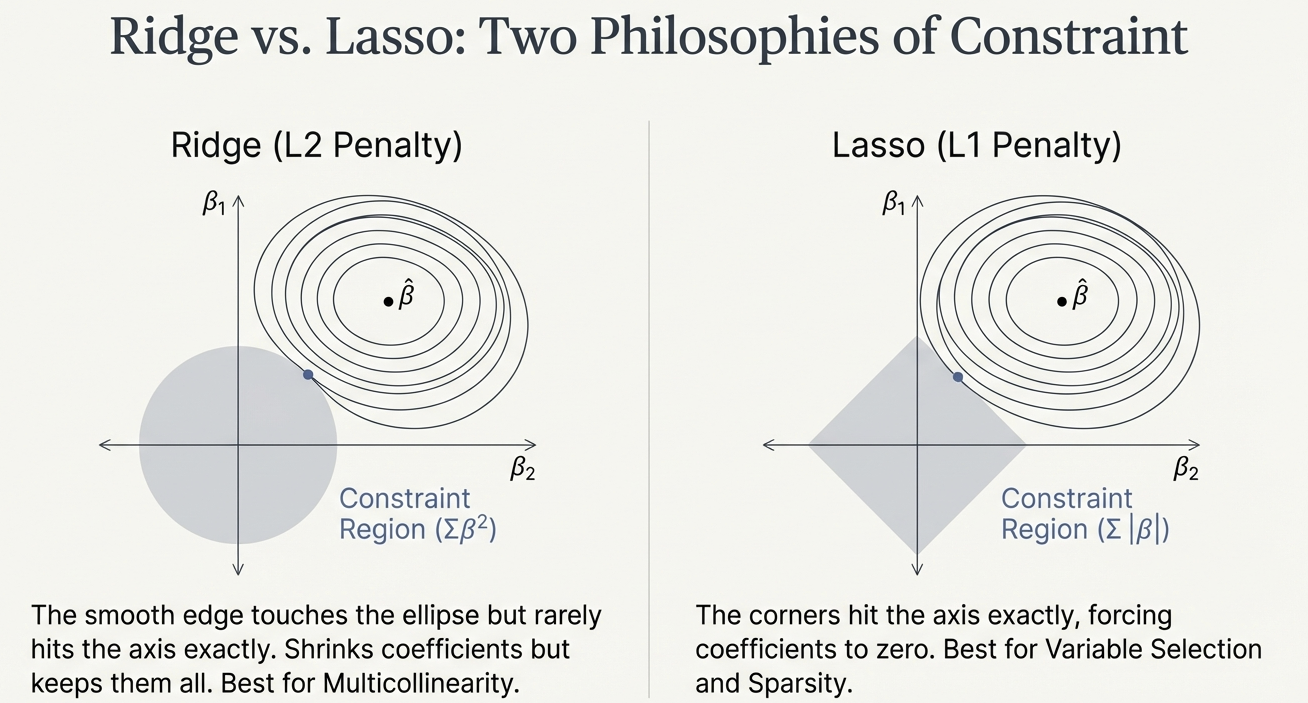

Geometric Intuition: The Circle

- Constraint Region: \(\sum \beta^2\) creates a circular constraint.

- The Result: The solution touches the circle but rarely hits the axis (zero) exactly.

When to Use Ridge?

- Best Use Case: High Multicollinearity.

- Example: Multiple survey items measuring the same construct.

- Handling Correlation: OLS would produce unstable estimates with huge standard errors.

- Ridge shares the credit among correlated predictors, shrinking them together.

Techniques

Section 4: LASSO Regression

LASSO Regression (\(L_1\) Penalty)

- The Formula: Adds the sum of absolute coefficients to the cost function. \[\dots + \lambda \sum |\beta|\]

- Behavior: * Forces coefficients exactly to zero.

- Performs Variable Selection automatically.

Geometric Intuition: The Diamond

- Constraint Region: \(\sum |\beta|\) creates a diamond-shaped constraint.

- The Result: The corners of the diamond hit the axes.

- Hitting an axis means the coefficient for that variable becomes zero.

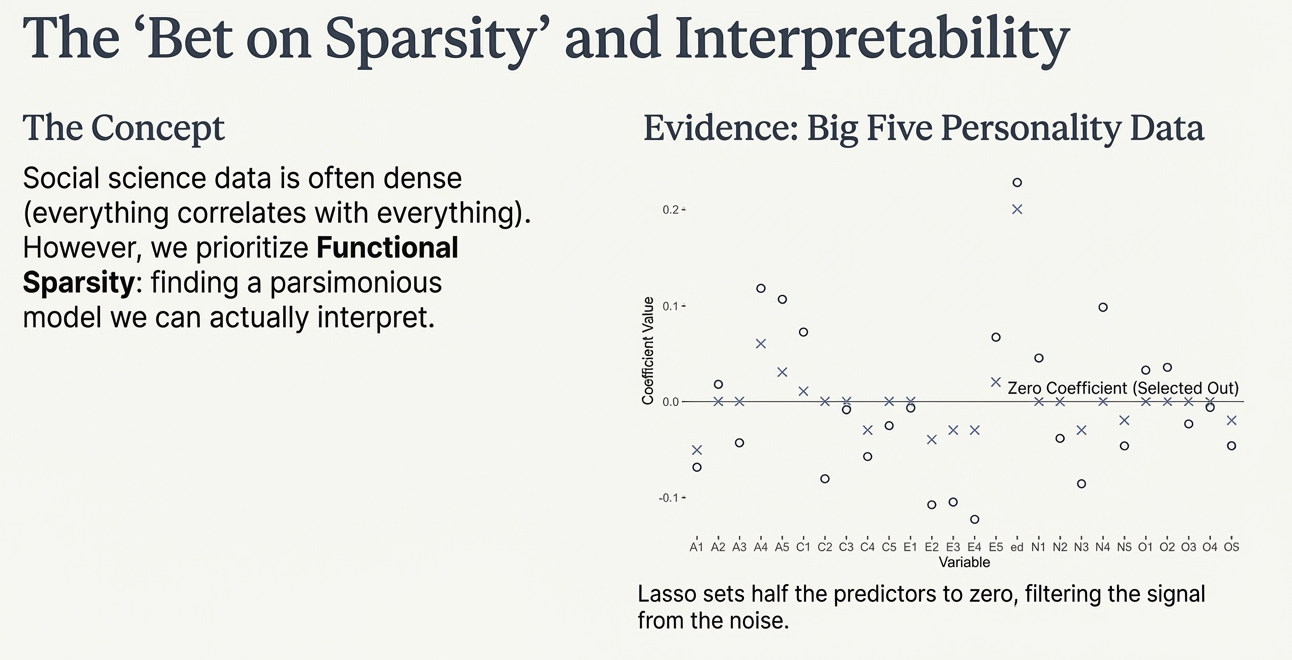

The “Bet on Sparsity”

- Assumption: The underlying truth is “sparse”—only a few variables truly matter.

- Reality in Social Science: Data is often dense (everything correlates with everything).

- Functional Sparsity: We prioritize a parsimonious model we can actually interpret.

Example: Personality Data

- Context: Predicting an outcome using Big Five personality items (\(p=25\)) + Education.

- Result: LASSO sets nearly half the predictors to zero.

- Benefit: Filters the signal from the noise, leaving a cleaner model.

Implementation

Section 5: Practical Application

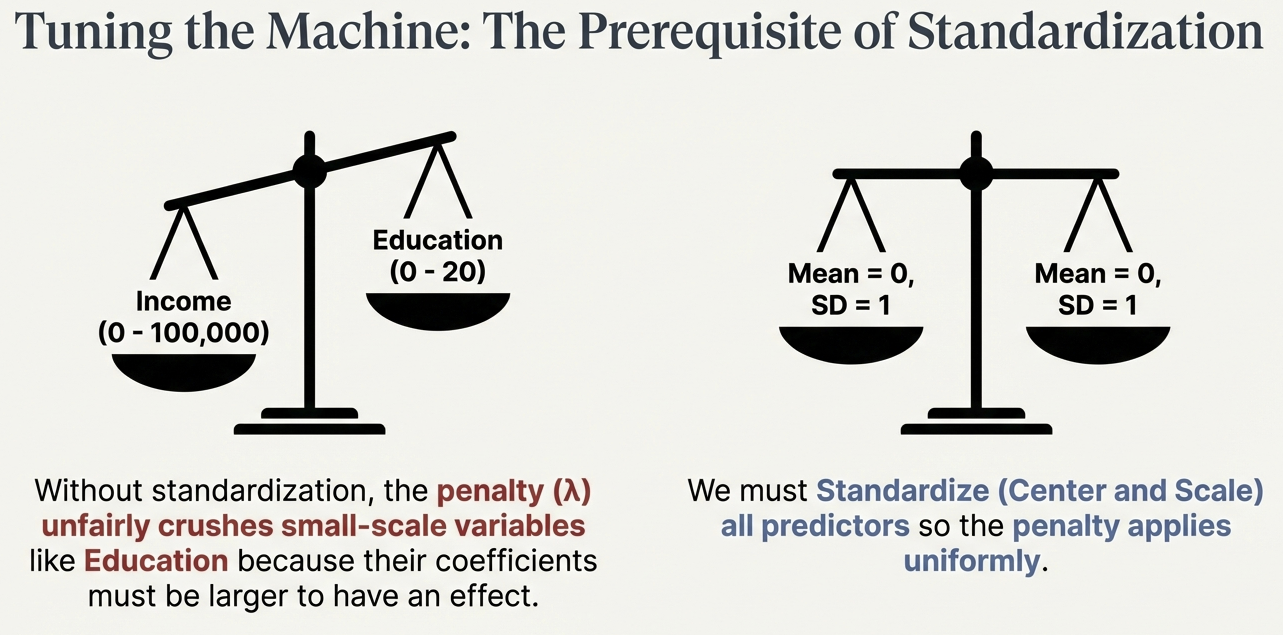

Prerequisite: Standardization

- The Problem: The penalty is uniform. Large-scale variables (Income) have small coefficients; Small-scale variables (GPA) have large coefficients.

- The Consequence: Without scaling, the penalty unfairly crushes variables with small natural scales.

- The Fix: Standardize (Center and Scale) all predictors to Mean=0, SD=1. Categorical variables must be dummy coded before standardization.

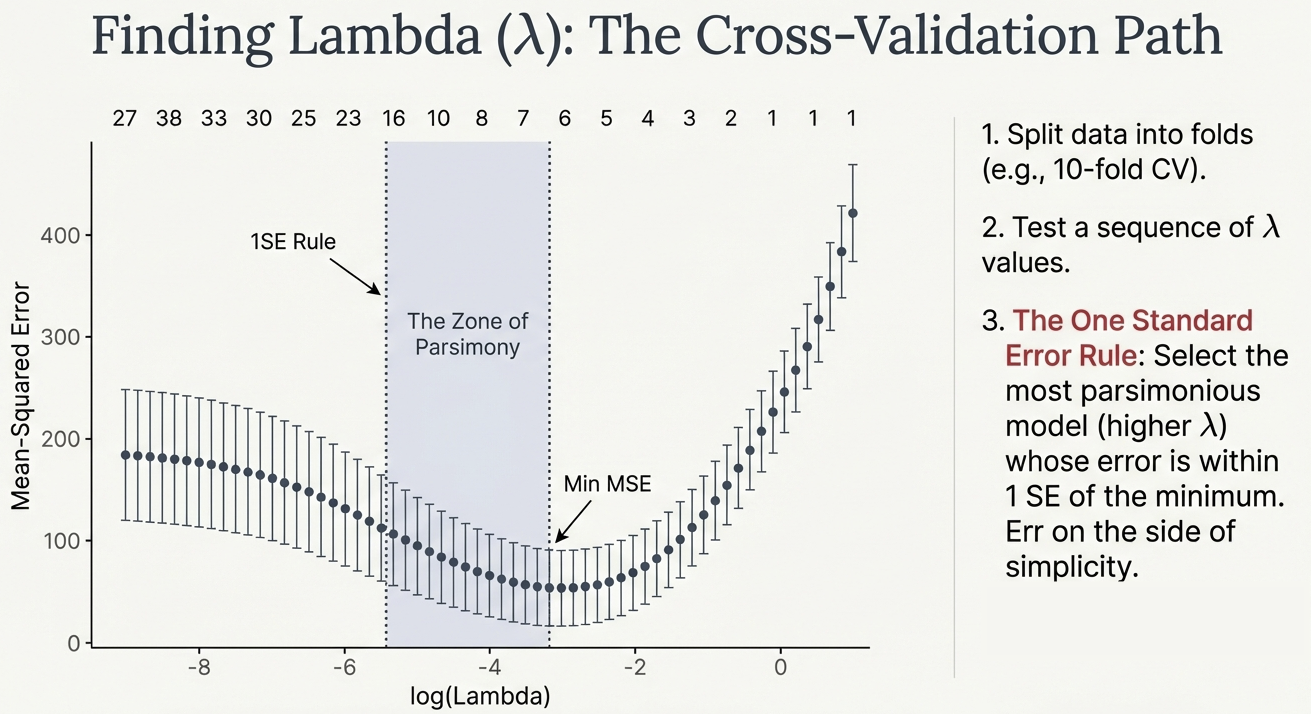

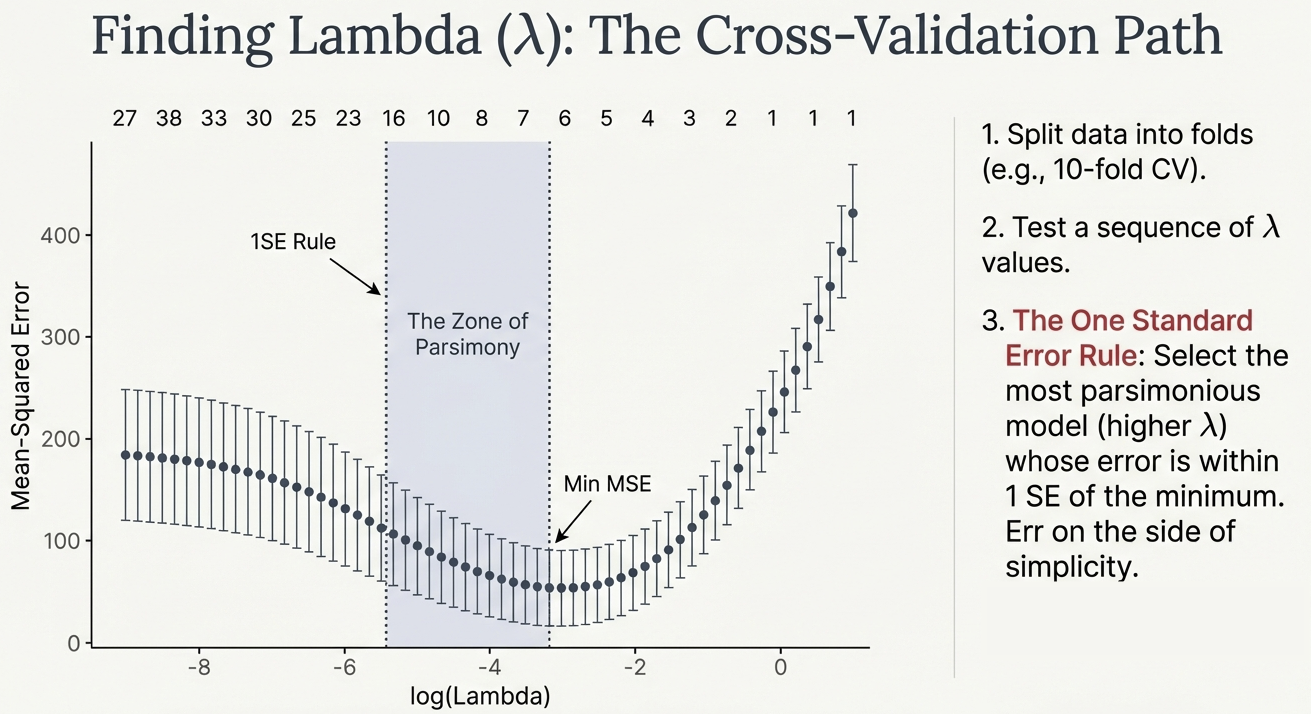

Choosing Lambda: Cross-Validation

- Process:

- Split data into folds (e.g., 10-fold CV).

- Test a sequence of \(\lambda\) values.

- Calculate Mean Squared Error (MSE) for each \(\lambda\).

- Visualization: The “CV Path” shows error changing as complexity changes.

The “One Standard Error Rule”

- Min MSE: The \(\lambda\) value that minimizes error mathematically.

- 1SE Rule: Select the most parsimonious model (higher \(\lambda\)) whose error is within 1 Standard Error of the minimum.

- Why? Err on the side of simplicity. If a simpler model is statistically indistinguishable from the complex one, pick the simple one.

Advanced Methods

Section 6: Extensions

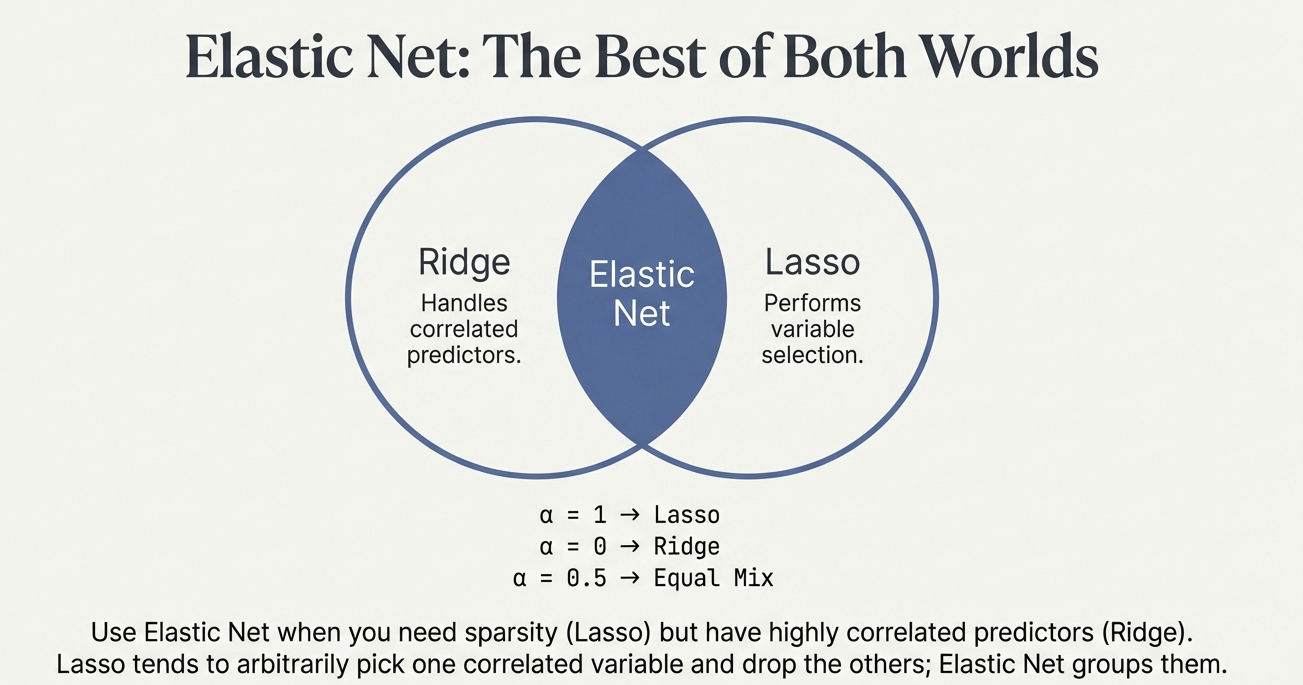

Elastic Net: Best of Both Worlds

- The Limitation of LASSO: If variables are highly correlated, LASSO picks one arbitrarily and drops the rest.

- The Solution: Elastic Net mixes L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) penalties.

- \(\alpha\) parameter controls the mix (\(\alpha=0.5\) is equal mix).

- Outcome: Performs selection (Lasso) but keeps correlated groups together (Ridge).

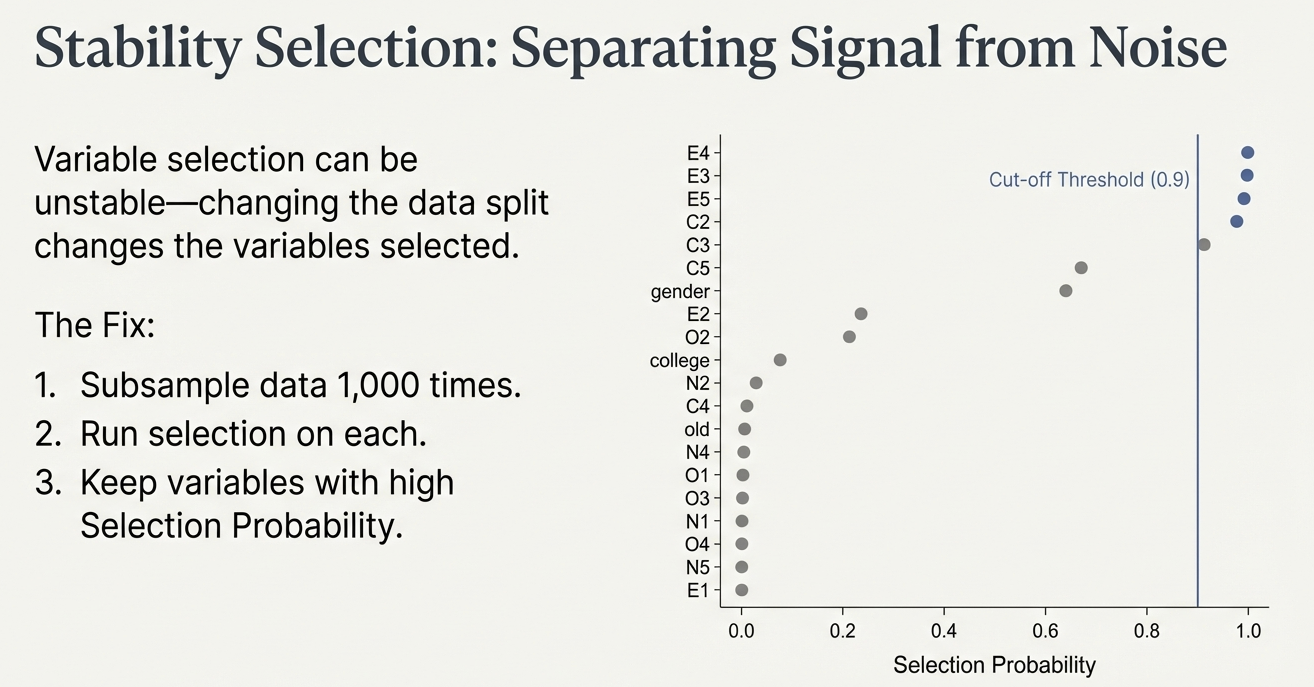

Stability Selection

- The Problem: Variable selection can be unstable. Changing the data split slightly changes which variables are picked.

- The Fix:

- Subsample data 1,000 times.

- Run selection on each subsample.

- Keep variables with high Selection Probability.

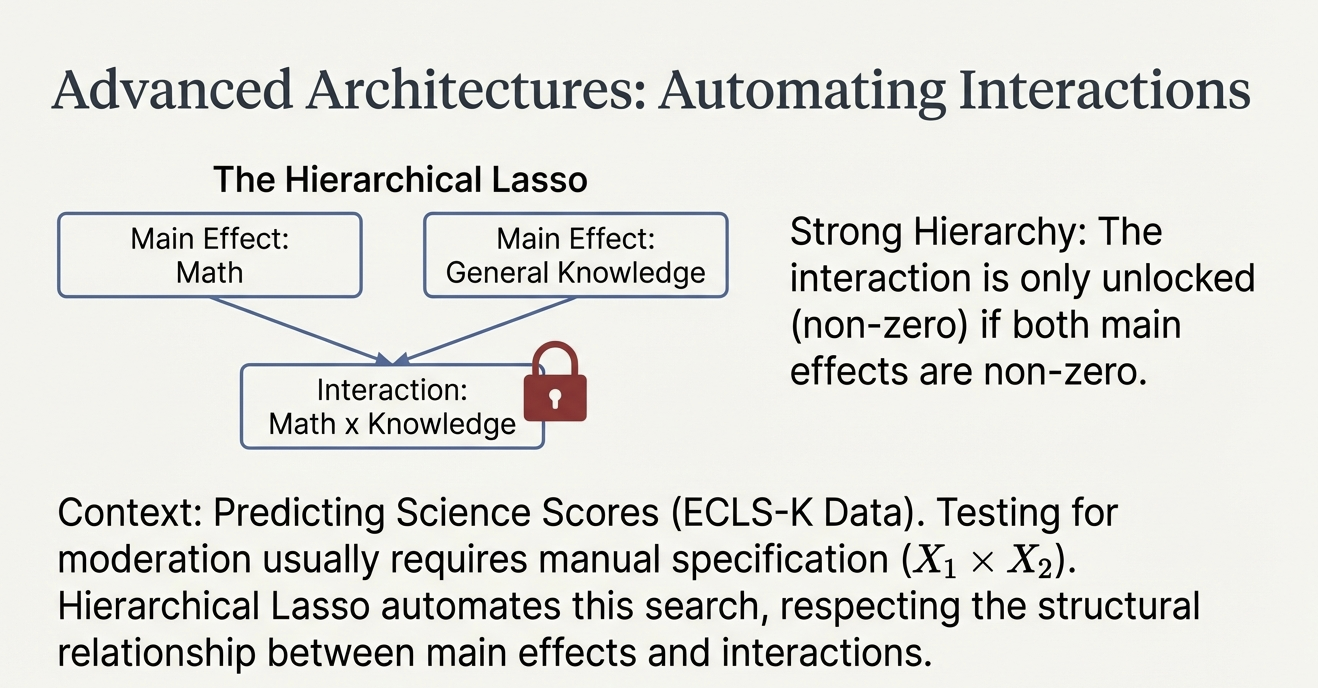

Hierarchical LASSO: Interactions

- Context: Testing moderation (e.g., Treatment \(\times\) Prior Knowledge).

- Challenge: With many predictors, checking all interactions is impossible manually.

- Solution: Hierarchical LASSO automates interaction search.

- Strong Hierarchy: An interaction is only “unlocked” if its main effects are also selected.

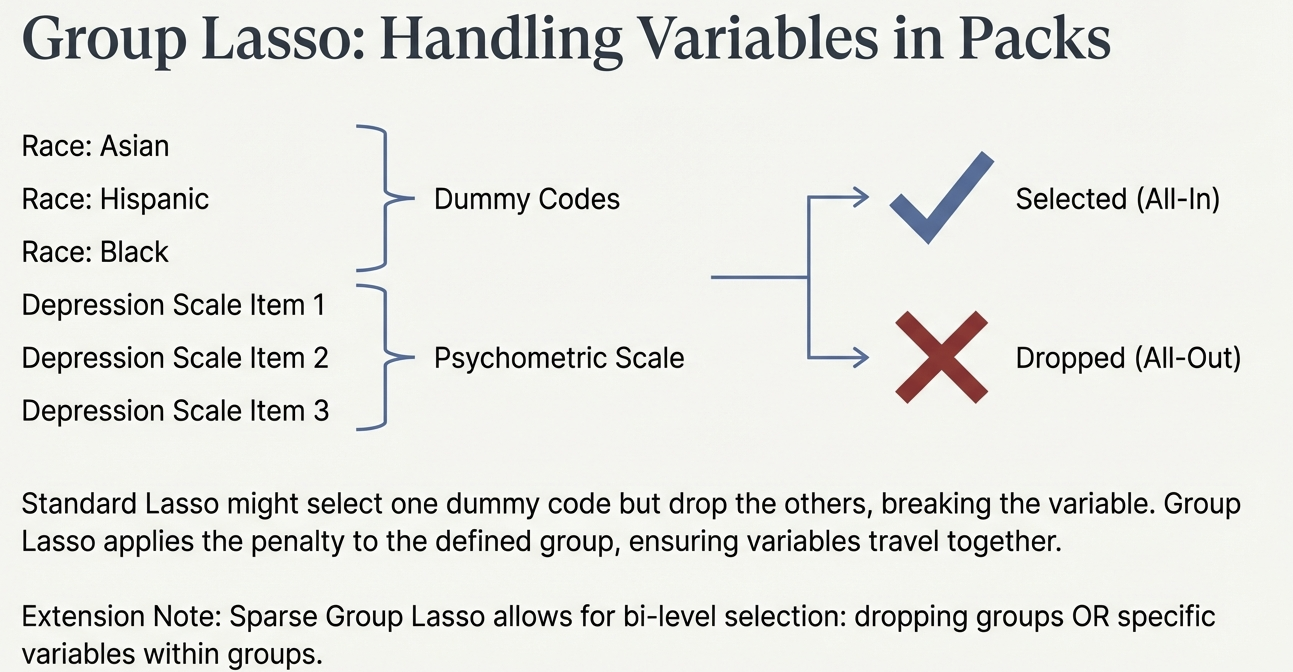

Group LASSO

- Context: Categorical variables (e.g., Race/Ethnicity dummy codes) or psychometric scales.

- Problem: Standard LASSO might drop “Hispanic” but keep “Asian,” breaking the variable structure.

- Solution: Applies penalty to the Group of variables. They are either all included or all dropped.

Conclusion: A New Standard

- Embrace Complexity: Regularization allows us to analyze high-dimensional data without being fooled by it.

- Filter Signal from Noise: It provides a principled way to reduce complex data to interpretable models.

- The Future: Moving towards robust, generalizable prediction in the Learning Sciences.